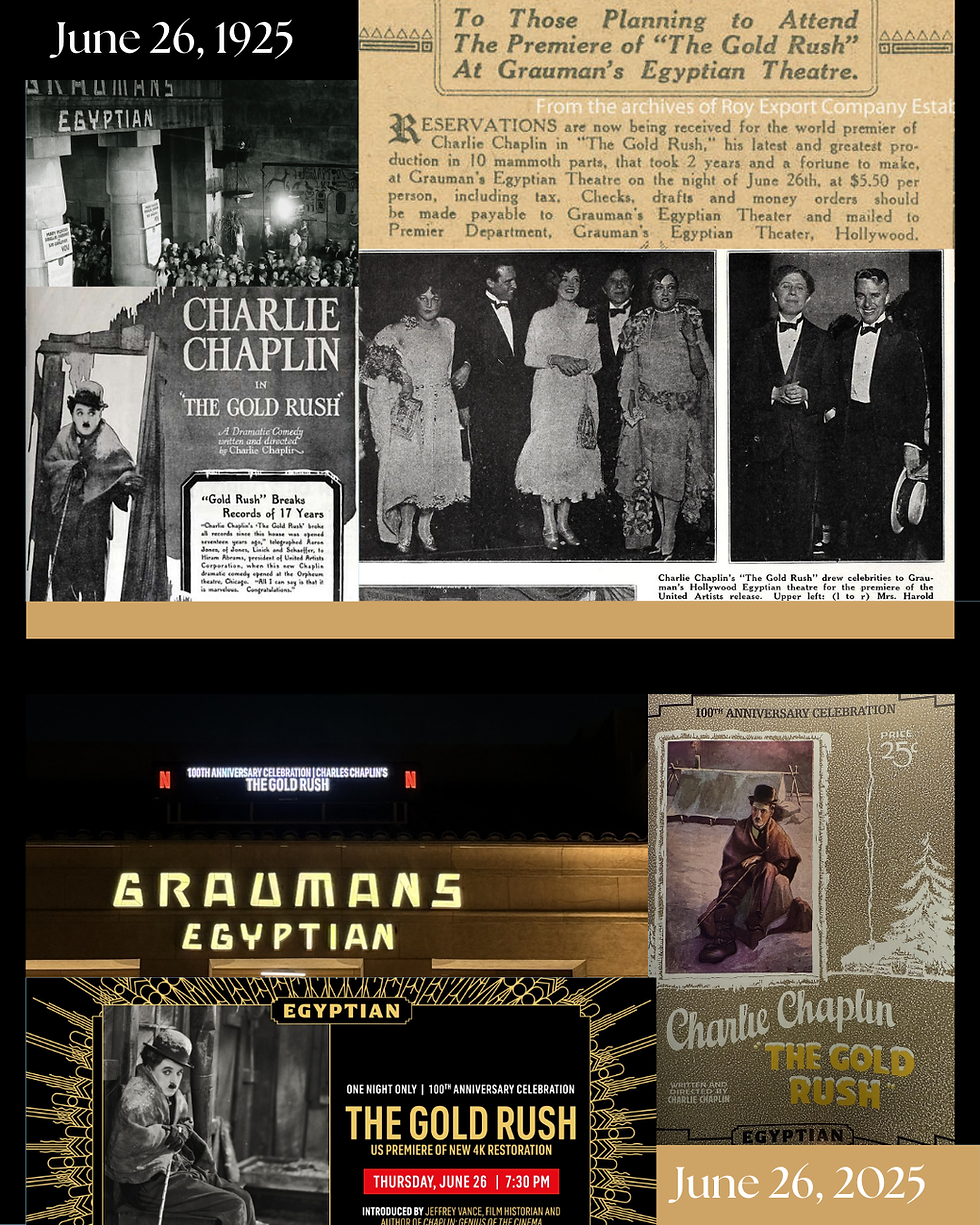

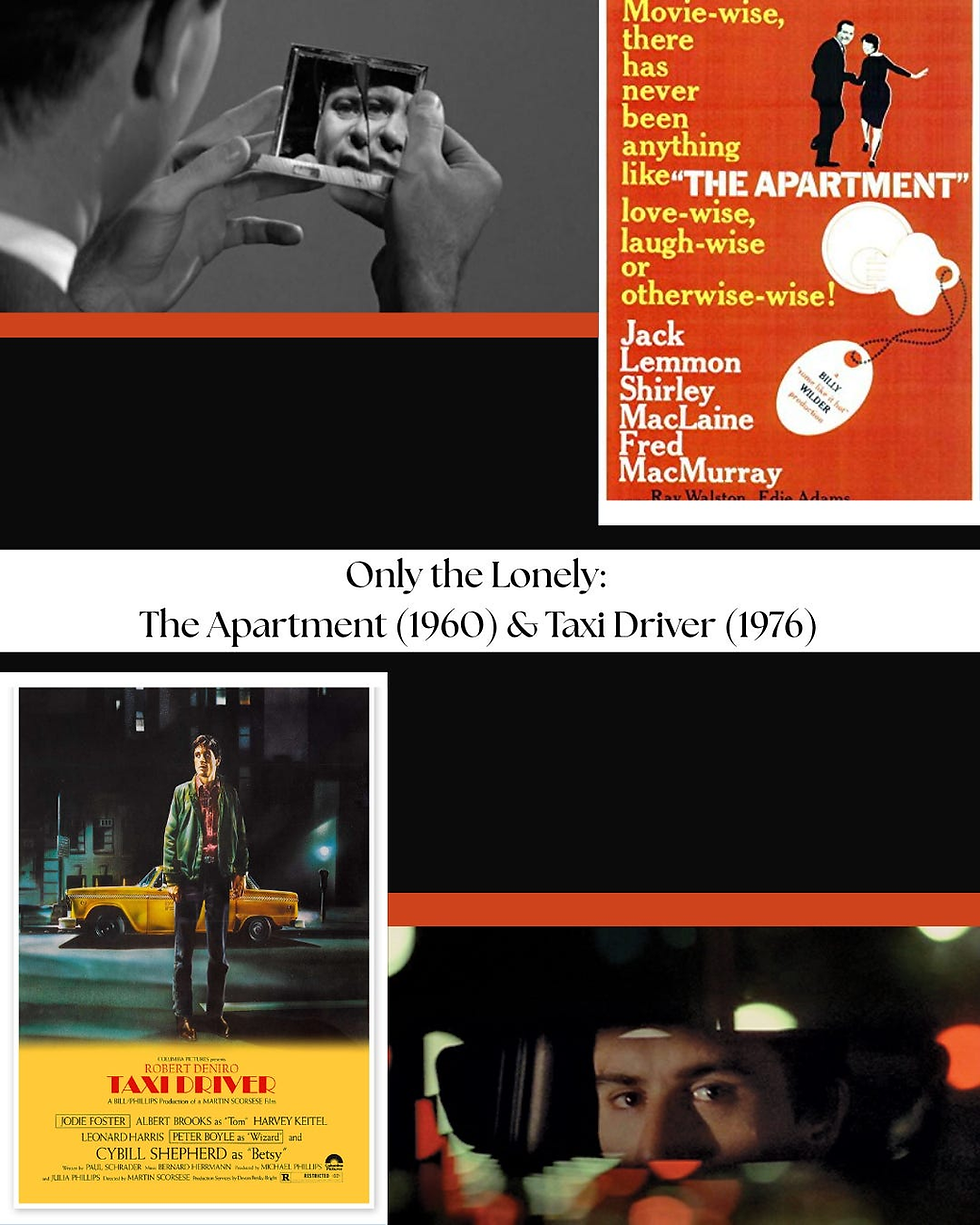

Only the Lonely: The Apartment (1960) and Taxi Driver (1976)

- Tina Ter-Akopyan

- 2 days ago

- 8 min read

By Tina Ter-Akopyan

Every day, you cross paths with thousands of people, even if you might not realize it. You scroll through hundreds of faces on your phone — people once in your class, people you never talked to in your life, people you were once close to but have drifted away. On the freeway and streets, millions of faces pass you by, all trapped in their cars or phones. All of us travel the same way but never seem to cross paths. The greatest irony of loneliness lies in our inability to realize that it’s a universal feeling which bonds us together.

In the United States, where self-reliance and individualism are revered as honorable qualities, loneliness is dismissed and even stigmatized as a failure to embrace independence. However, filmmakers Billy Wilder and Martin Scorsese are unafraid to explore and tackle the dark and uncomfortable nature of loneliness hiding underneath America’s veneer in their respective films The Apartment (1960) and Taxi Driver (1976). On the surface, The Apartment, a romantic dramedy, and Taxi Driver, a dark psychological thriller, represent the vision and craft of two completely different artists. A leading filmmaker of the Golden Age, Wilder adhered to more traditional filmmaking techniques but challenged Hollywood narratives through his cynical and grounded stories. Meanwhile, Scorsese was at the forefront of the new and ambitious filmmakers emerging in the 1970s through his bold and experimental style. Despite representing contrasting eras of Hollywood, these directors share a distinctive, daring, and truthful portrait of isolation that pushes the audience to confront and reflect upon their own feelings of loneliness without any shame.

To paint this portrait of urban loneliness, Wilder and Scorsese turn to New York City. Although it stands as one of the most populated cities in the country, it is easy to lose oneself and become invisible among the massive sea of people. In both films, the city becomes a key character, pushing C.C. Baxter (Jack Lemmon) and Travis Bickle (Robert DeNiro) deeper into a lonely abyss.

C.C. BAXTER

“On November 1st, 1959, the population of New York City was 8,042,783. If you laid all these people from end to end…, they would reach from Time Square to the outskirts Karachi, Pakistan.”

The Apartment opens with a sky-high view of New York City and slowly moves down into one of the skyscraper buildings, where hundreds of workers march inside like an army of ants. Leading the scene is our narrator and protagonist C.C. Baxter, a lonesome bachelor who works in the building as an insurance clerk. Once the workday ends, all 31,258 workers rush out, except for Baxter, who stays among the never-ending rows of empty desks and chairs. Lending his apartment to his bosses and their mistresses as a hideout, Baxter kills time by throwing himself into work or aimlessly wandering the streets of the city.

To capture Baxter’s bleak reality, cinematographer Joseph LaShelle relied on the newly developed Panavision anamorphic lens. While filmmakers used Panavision for Technicolor musicals and epics, LaShelle saw the potential to use the wide range lens to capture the vastness of the city and emphasize Baxter’s loneliness. Whether Baxter sits alone in a crowded bar on Christmas Eve or at his office desk among a sea of employees, the deep focus of the wide lens captures the background interactions surrounding Baxter, who is both among the crowd but also an outsider. The decision to capture the city through black-and-white cinematography also immerses the audience in Baxter’s mundane world, where he struggles to find any color and meaning in his life.

In contrast, Taxi Driver starts in the lower depths of the city, revealing the streets filled with grime, smog, and blaring neon lights. Following LaShelle’s style, cinematographer Michael Chapman relies on wide shots to establish the overwhelming enormity and emptiness of the city. As Travis begins driving his taxi back and forth among the slippery wet streets, Chapman captures the grey cloud of hopelessness shrouding the city and fueling Travis’s insanity through his mix of both desaturated and bold colors. The blur of neon signs and faces from people on the street creates a sense of disorientation and disconnect, which immerses the audience into Travis’s consciousness. Chapman also effectively uses a shallow depth of field to isolate Travis among the crowd and showcase his alienation from the rest of society.

TRAVIS BICKLE

“Loneliness has followed me my whole life. Everywhere. In bars, in cars, sidewalks, stores, everywhere. There's no escape. I'm God's lonely man.”

On the surface, Baxter and Travis couldn’t be any more different. Baxter, with a clean-shave and a tailored suit, puts up a charming and positive demeanor. Meanwhile, Travis, rugged and disheveled, hides a quiet uneasiness and awkwardness. Nonetheless, both characters wear the same cloak of invisibility. They hold a deep desire for connection but have come to accept loneliness as a way of life.

Despite being placed in their point of view, Baxter and Travis remain a mystery throughout the film. Wilder and Scorsese intentionally reveal minimal information about each character’s past to present an emotional enigma for the audience to decode. Working day and night, Baxter and Travis throw themselves into their jobs, not because they are passionate, but rather because it distracts them from the emptiness in their lives. No matter their efforts, their jobs offer no sense of community, no creative outlet, and no opportunity for self-expression. Instead, they simply become a vessel for labor and exploitation. Through this representation, Wilder and Scorsese provide a subtle yet searing reflection of how a capitalistic economy thrives on the isolation of workers. The less distracted they are by the outside world and their personal lives, the more their job becomes their sole identity. While Baxter and Travis try to connect with their co-workers and find community among them, both feel disconnected and distant from their way of life.

FRAN KUBELIK

“Some people take, some people get took. And they know they're getting took and there's nothing they can do about it.”

With work not fulfilling them, both characters hopelessly turn to love to find meaning in their lives. Stalking Betsy (Cybill Shepherd), who works at the campaign office of a presidential candidate, Travis idealizes her as a woman who will understand and care for him. Summoning his confidence, Travis barges into her office and asks her out. However, their relationship immediately goes awry when he takes her to pornographic theater for their first date. When Travis tries to call Betsy, he faces a cold rejection. In this famous scene, Scorsese utilizes a long shot that slowly pans off screen from Travis at the phone booth to an empty hallway. Listening to Travis’s painful conversation off-screen, the audience feels a mix of discomfort and empathy, as he tries his best to save the relationship and find an escape from his loneliness.

TRAVIS BICKLE

“I realize now how much she's just like the others, cold and distant, and many people are like that, women for sure, they're like a union.”

Betsy’s rejection sends Travis into the deep end of his insanity, as she represented his only hope to find someone who would care for him. The rage and isolation that arises from his failure to connect with her confirms Travis’s belief he is truly alone in the world. Spiraling down a rabbit hole of obsession and hatred, Travis concludes that the only way he can force society to notice and respect him is through violence.

TRAVIS BICKLE

“I got some bad ideas in my head.”

In a similar manner, Baxter’s crush on Fran Kubelik (Shirely MacLaine), the charming elevator girl working in his building, epitomizes his dream of breaking out of his lonely life. Kind and attentive, Fran makes Baxter feel seen, compared to his other employees who only view him as a pawn. During the office Christmas party, Baxter hopes to court Fran and arrange a date. However, when she hands him her mirror to check how he looks, he realizes it’s the same broken mirror his boss Mr. Sheldrake (Fred MacMurray) had grabbed before leaving his apartment. Understanding that Fran is Sheldrake’s mistress, Baxter is left shocked, embarrassed, and enraged. In the broken mirror, we see Baxter’s face and confidence completely shattered. Hopeless and depressed, he spends the evening drinking his feelings away. While Travis’s isolation leads him down a path of violence, Baxter’s loneliness leads him into a state of passive existence. Finding no purpose or passion in life, Baxter feels empty and allows his bosses to take advantage of him, even if it hurts.

C.C. BAXTER

The mirror…it’s broken.

FRAN KUBELIK

Yes, I know. I like it that way. Makes me look the way I feel.

However, Fran is the one who ultimately breaks Baxter out of his passive and alienated existence. Finding Fran asleep on his bed when he arrives home from the bar, Baxter angrily tries to kick her out until he realizes that she has overdosed on sleeping pills. As Baxter spends all night nursing her back to health, he realizes how Fran faces the same loneliness and insecurities that he does. Through the traumatic experience, Fran and Baxter find in each other someone who can understand and empathize with their pain. This feeling of love and empathy empowers Baxter to finally take a stand and break free from his submissive acceptance of his bosses’ toxic behavior. When Baxter receives his dream promotion with the condition that Sheldrake can use his apartment for his affairs, Baxter quits and walks away.

C.C. BAXTER

“Just following doctor’s orders. I’ve decided to become a ‘mensch.’ You know what means? A human being.”

At the end, both Baxter and Travis seem to achieve what they desired throughout the film. Travis finally gained the attention he dreamt of by using his violent outburst to save a young girl, Iris (Jodie Foster), from a sex trafficking ring. Meanwhile, Baxter found a true companion in Fran. Despite this sense of resolution in both films, Wilder and Scorsese end on drastically different notes that change how we view the future of these characters.

In The Apartment, Wilder integrates an underlying sense of optimism. Learning that Baxter quit his job after Sheldrake wanted to bring Fran back to his apartment, Fran finally sees through Sheldrake’s empty shell and runs towards Baxter. Wilder does not indulge the audience with an overly romantic ending where Fran and Baxter seal their love with a kiss. Instead, we witness a spark of hope that Baxter and Fran can help each other escape the depths of loneliness.

C.C. BAXTER

“You hear what I said, Miss Kubelik? I absolutely adore you.

FRAN KUBELIK

“Shut up and deal…”

On the surface, Travis also seems to receive his happy ending, as society acknowledges him and views him as a hero. Reading his name in the newspaper, receiving a letter from Iris’s family, and being congratulated by his co-workers, he finally feels seen. However, as Travis goes back into the routine of driving his cab, the audience witnesses the sad truth. No matter the attention or fame, he still lacks the ultimate cure for his loneliness: a real connection. Serendipitously, entering his cab in the final scene of the film is Besty. Travis, with a grin on his face, acts humble when Betsy asks about his “heroism.” Once he drops her off, he looks past her from the rearview mirror and she seems to instantly disappear, leaving the audience to wonder if the interaction was real or all a manifestation of Travis’s descent into insanity. The movie ends with a sense of uneasiness and discomfort, as we are left to wonder in what shape and form will Travis’s loneliness manifest itself next.

Loneliness has always haunted society (now more than ever in this digital era). The Apartment and Taxi Driver provide a critical and searing reflection of how loneliness can destroy a person’s will, sanity, and dignity. Wilder and Scorsese use these seemingly ordinary characters to shed light on how the lack of community and support leads people down a dangerous path of isolation. By tackling this subject, both Wilder and Scorsese show that loneliness is a universal plight but one that we can overcome by truly caring for one another.